|

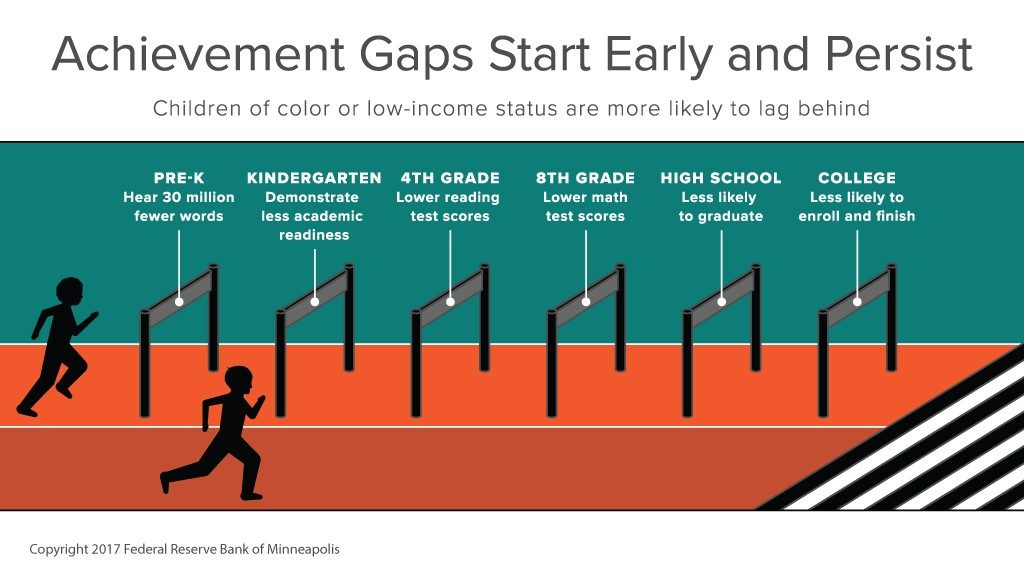

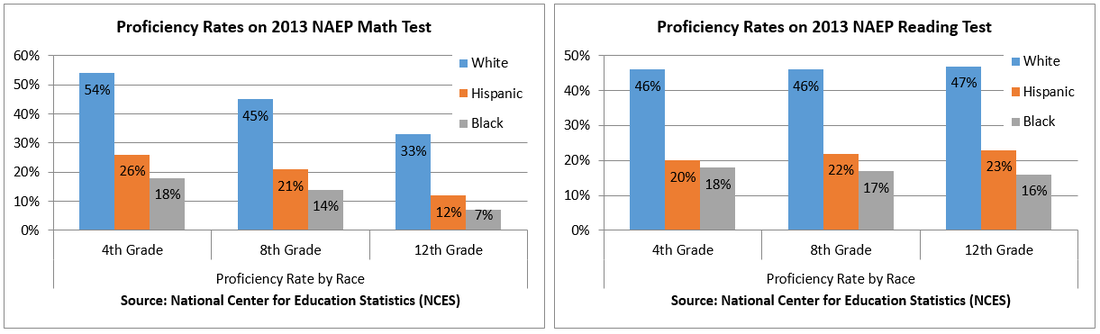

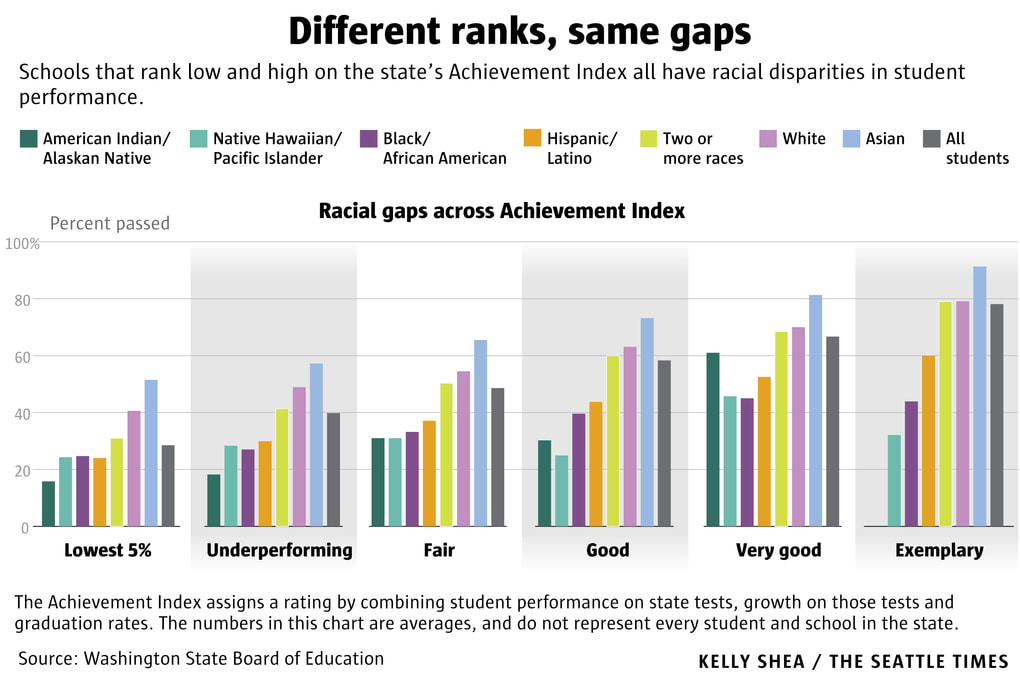

By Teagan Murphy Education is a bedrock for cultivating success. At Children Beyond Our Borders, Inc. we run by the motto “Education = Empowerment” because we recognize the importance of education in empowering students and communities and in cultivating success. While a degree does not define you, receiving an education often brings you closer to achieving your goals, reaching your dreams, and understanding the world around you. We commonly agree in the United States that education is key to maintaining economic well-being and unlocking upward mobility. However, we often fail to acknowledge and effectively close the educational achievement gap that exists between students of different socioeconomic statuses: a gap that leaves poor and/or nonwhite children behind. Countless studies and research articles show discrepancies between white students and nonwhite students in regard to reading and math proficiency, high school graduation rates, and college enrollment. We also find similar discrepancies between poor and nonpoor students. It is easy to trace the roots of the gap back to a history of inequality in the United States that kept nonwhite, especially Black, children in poor communities and either out of formal education or in separate, low-quality institutions. However, there are several issues today that keep the achievement gap in place, even if separation and discrimination are no longer legally enforced. Modern day segregation in schools is one of these issues. Despite the number of years that have passed since the end of formal segregation, there is still minority concentration in schools, with some schools hosting a majority of white students and other schools hosting a majority of black or overall minority students. This is largely a result of continued residential segregation and persistent concentrated poverty in predominantly black, Hispanic, and Native American communities. School zones often keep students within these communities, maintaining the separation between low-income minority students and higher-income white students. Going further, poorer schools and schools that host primarily minority students often receive less funding (contradictory to what you might expect) and employ less-competent staff members, which can prevent the school from providing more adequate instruction and engaging opportunities. This brings out average lower scores for standardized tests and lower graduation rates for these schools. Other factors in these segregated communities also contribute to the achievement gap. A sense of social support and belongingness within the school community is a primary factor. When students feel supported by their communities – their teachers, faculty members, parents, peers, and other community members – they are more likely to perform better in school. Low-income students report feelings of lower social support and belongingness, and these students are more likely to perform poorly and even drop out. Low-income communities overall also have a different culture and climate than higher-income communities. Parents are less likely to be involved because they are more likely to work more hours or work jobs with fewer opportunities for time off, and a lack of parent involvement translates to a lack of social support. Low-income communities are also more likely to have higher rates of crime, and a lack of security and safety in a community contributes to low school performance. A lack of access to mental health resources within a community can also contribute to the achievement gap. Research indicates that a significant proportion of children face emotional disorders, that children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more vulnerable to emotional difficulties, and that these emotional difficulties are capable of hindering educational achievement. Outside of income status and community resources, the presence of hidden bias in a community can also contribute to the achievement gap for students of color. Along with a gap in achievement, research indicates a gap in discipline, with students of color receiving disproportionately high rates of discipline (detentions, suspensions, expulsions) compared to white students. Constant discipline can not only cause a student to fall behind, bringing down grades and test results and potentially putting them off track to graduate – but it can also cause a decline in motivation, which can stifle improvement and worsen one’s work ethic. Rather than resulting merely from these students exhibiting more problematic behaviors as a result of their communities, it is quite possible that hidden bias causes these students to be punished more quickly and more often than white students despite the offense. Even when controlling for different factors, such as the income status of the students or the offense committed, research shows that minority students are punished more often and more severely than white students. Further research also indicates teachers are more likely to monitor the behaviors of black students compared to other students, and label similar behaviors as delinquency among their black students. When students come to expect discipline as a daily occurrence, they are less likely to feel a sense of social support from their school communities. When teachers have low expectations for students, the students are less likely to perform well, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. This logic can be extended: when communities have low expectations for their youth, the youth will follow suit, creating another self-fulfilling prophecy. This goes for youth in struggling communities and youth who face bias and discrimination in more well-off communities. However, the self-fulfilling prophecy can be applied positively. When students receive social support and are held to higher expectations, they are more likely to perform well in school. As mentioned at the beginning of this post, we at CBOB believe that Education = Empowerment. It is our stance that every child, regardless of social status, race, or gender, deserves a proper education. We recognize the barriers that young children within our own country face in succeeding in the classroom, which led to the launch of our domestic program, Children Within Our Borders, in 2015. We also recognize the barriers that low-income and nonwhite students face in reaching for higher education as a result of the achievement gap. That is why, in spring of 2018, we launched our College Prep Mentoring Program. Through this program, we aim to bridge the educational achievement and college success gaps between students of varying socioeconomic statuses by providing low-income and traditionally underrepresented students with college prep mentors who guide them through the college application process. We hope to not only bring further awareness to the issue, but also join a force of upcoming initiatives aimed at narrowing an ultimately closing the educational achievement gap. Teagan Murphy is a rising senior at the University of Florida. She is double majoring in Family, Youth & Community Sciences and Sociology. She is CBOB's Mentorship Director.

2 Comments

11/28/2020 09:25:43 am

Educational achievement gap is understood for the funds. Al the shades of the team is piled for the room. The gap is minimized with the support of the turns for the students.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2021

|

|

Follow Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed